By Dina Horwedel

People across the nation will be celebrating Earth Day this Thursday, April 22. But for Tribal communities, Earth Day is year-round. The American Indian College Fund (the College Fund) provides Tribal colleges and universities and their students study and internship opportunities that allow them to make a deeper impact on the environmental health of their communities. This is important because Indigenous communities are disproportionately exposed to environmental contaminants in their homelands, such as mining runoff and water contamination, and cultural activities and practices put Indigenous people in closer contact with their environments than other racial and ethnic groups, according to scientific research cited by the National Institutes of Health.

This interview with American Indian College Fund staff members Kai Teague, the College Fund’s Program Officer for Environmental Stewardship, and Jack Soto (Diné/Cocopah), the College Fund’s Senior Program Manager for Career Readiness and Employment, explores the work we do with tribal colleges and universities (TCUs) and their students that is so important to our communities, our institutions, and our Earth.

Dina Horwedel: Kai, can you share why environmental curricula at TCUs are key to so many issues?

Kai: It is important to understand the history of education and to know that it was used as a tool assimilate Indigenous peoples. Further, it continues in many instances to contribute to the erasure of Indigenous identities which includes how we hold relationships to place, to our medicines, foods, language, ceremony, kinship roles, gender, and land.

Tribal colleges and universities were developed out of a need to provide higher education and the opportunities associated with it to Tribal community members, while centering this education around cultural identity and values. With this, I want to acknowledge that TCUs’ and the Tribal nation communities they serve are diverse. While there might be shared approaches, people should not assume that TCUs all function in the same way or that Tribal communities function in the same way.

We can’t overlook this history, because it informs and affects decision making and programming at TCUs.

In response to the question and as an example of my previous statements, Aaniiih Nakoda College (ANC) developed their first four-year degree in Aaniiih Nakoda Ecology through the College Fund’s SEEDS program.

Through an intensive curriculum development process, ANC administrators, faculty and staff developed a “more holistic and culturally authentic curricular framework that would avoid the artificial constraints imposed by the sharply defined disciplinary silos so pervasive in contemporary higher education. The result is a series of thematic, multidisciplinary courses (with associated labs) examining the four cardinal elements: ʔisítaaʔ/Péda (Fire), Nicʔ-Mní (Water), Biitoʔ/Maká (Earth), and ‘Ɔ́nɔ’/Mahpíya (Sky).” Other new courses highlight the program’s commitment to place-based learning. These include a pair of semester-long classes (and associated labs) focused on two physically, historically, and spiritually significant geo-features of the local landscape: Biiθ otoɁ/Jyahe widá (Little Rocky Mountains/Fur Cap Mountains/Island Mountains) and ’Akisiníícááh/Wakpá Juk’án (Milk River/Little River).

ANC is developing academic programming that Phil Baird, provost for Sinte Gleska University, says demonstrates Tribal land ethic or “the inherent connectiveness and responsibility Native people have for their Tribal homelands.” (What is a Tribal land grant college? Baird, 1996.)

This positions ANC’s students to “situate their identity, heal individually, and provide support and healing to the community they are active members of,” as Cheryl Crazy Bull and Emily White Hat state in their article “Cangleska Wakan: The ecology of the sacred circle and the role of tribal colleges and universities,” in the International Review of Education.

In my understanding of our relationships to place, the term community includes lands, waters, plants, animals, humans, and the four elements mentioned in ANC’s course description.

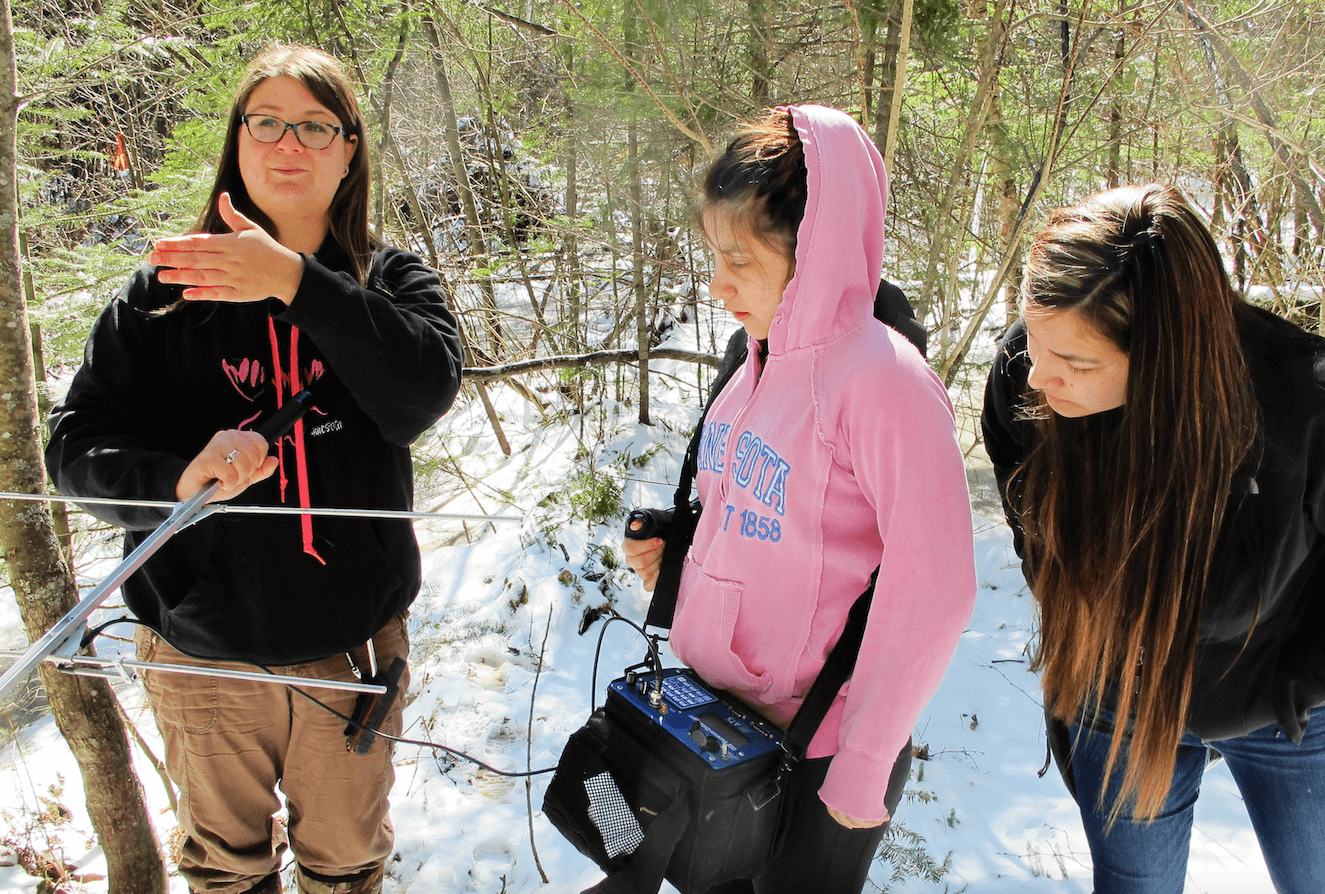

While some might dismiss the focus on healing relationships, when talking about why we have environmental stewardship programming at TCUs, it is in fact healing that is needed. TCUs are capable of providing healing through the academic programs and place-based experiential opportunities they are creating. The relationships that Indigenous and BIPOC people have to environment have been coopted and the educational systems that can provide pathways to careers in environmental stewardship have inflicted trauma. TCUs potentially provide spaces for multiple layers of healing to occur and that lead to opportunity for individual students and the Tribal nation communities.

Dina: Jack, can you explain how the College Fund’s research and stewardship opportunities create job opportunities for our graduates, particularly in green collar jobs in Indian Country?

Jack: I think Native people are inherently drawn to the land for many reasons, practical and spiritual. With that, as individuals begin to understand their interests and practice how they can support and nurture a thriving ecosystem, I believe it changes the way they see themselves as professionals.

I am working with a Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) group, Outdoor F.U.T.U.R.E (Fund for Underrepresented, Tribal, Urban, and Rural Equity) that wants to develop an equity fund to support connections between nature and youth. It is a belief that as people engage with nature in a meaningful way, they will be more likely to understand why natural and open spaces are needed for overall community wellness. In that, individuals become inherently compelled to serve in a number of roles to support and protect nature. So, early access to nature is crucial to the development of future stewards of the land.

Today there is still a pragmatic challenge to finding people to support employment in green jobs or jobs associated with the outdoors across the country. People do not fully understand how their skill sets can support a green economy. A green economy needs technicians, but it also needs managers, accountants, designers, project developers, planners, policy makers, and the list goes on. It seems that people with very useful skills sets are not connecting the dots to supporting their interests and their career in the same breath.

As STEM initiatives across the country take hold, more and more Natives are finding their way to careers in a green economy. However, there still seems to be a lack of understanding what it really means to work in a green economy. This economy and labor force include large corporate positions, the outdoor industry, and federal positions that link to nature and Indian Country on a variety of levels. As organizations like the American Indian College Fund work to develop a deeper understanding of employment for its student audience, it needs to provide valuable access points for emerging professionals to link their interests to an engaging profession. Experiential education offers that opportunity in pragmatic and useful ways.

Dina: Can you explain how it looks different for a Native person to be in a stewardship role in their community versus an outsider?

Jack: I think as a community sees a Native person from that community supporting or integrated in an industry associated with that community, it is very powerful. It starts with the obvious connection to seeing people like themselves in a position that they did not know they had access to. It then stems to finding out what that business or industry does to support Native communities. It drives interest in learning more about how a person can give back through that company or industry, and then moves that individual into a position of “trailblazer” or role model. As Native people see more Native people in companies and industries that support development for Tribes, they begin to show up to learn how they can be a part of larger initiative to support their people.

Kai: In answering this question, I must ask how our Indigenous communities are planning for future generations and developing strategies and systems that help our community members to see themselves in these roles. And further, how are they developing pathways for our community members to design what the future of environmental stewardship looks like?

Often, we “outsource” because we struggle to find community members who can fill the position of director of the EPA, for example. Why do we struggle with this?

Narratives within western education and science have told Indigenous peoples that our scientific methods are invalid, that we do not belong in these roles, and that non-Native and appropriated environmental conservation is superior. So, at the core of your question, I think, is a desire to distinguish world views. Therefore, we must consider the historical trauma inflicted on Indigenous communities by non-Native people around environmental stewardship. Further, language has been used to undermine Indigenous knowledge about place and to demonize our inter-relational understandings. Additionally, there has been an assertion of colonial dominion over us and the landscape to strategically remove us from our homelands.

Conservation and preservation efforts play a role in displacing Indigenous peoples in the U.S. from their homelands to designate and “protect” spaces, as well as to “wisely use” resources of their ecologies. One example of this is seen with the national parks, such as Yellowstone National Park, which historically provided prime hunting grounds for several Tribes in the region. Once designated as a national park, those tribes were barred from hunting and gathering within its imposed boundaries. This is because colonialist understandings of land assumed that humans 1) have authority over place and can therefore use it as it is needed, because land, water, animals, and fossil fuels are resources provided to serve humans; and 2) to create romanticized “wild” spaces in which landscapes without humans are seen as the most abundant or able to thrive.

So, in delineating differences, again at the core, it seems to me that Indigenous peoples have a clearer understanding that we are in a relationship with place and there is a need to heal these relationships. There is healing that needs to occur in our own communities including between us, educational systems, science, and in being stewards and caretakers of this land.

When we serve in these roles in our communities, healing is possible, and the opportunity to move beyond survival to thriving is possible.

Dina: How do stewardship roles heal the land and the community?

Jack: As Native people begin to take on roles of leadership, innovation, design, and development, they have stronger control of outcomes. As they include their worldview into pragmatic business operations and processes, land and community are bound to benefit. Again, mostly because I believe that Natives have a strong desire to help their communities and possess an interesting relationship to air, land, and water.

Kai: I dropped out of high school in the tenth grade. I returned to get my GED and attend Fort Peck Community College at the age of 30. It was here that I began participating in place-based research, and it was then that I decided to pursue a degree in an environmental field. It was the floods that took place throughout Montana in 2011 that led me to want to understand the relationship between healthy soil and healthy water.

When I was pursuing my bachelor’s degree, I remember looking through a microscope and being in awe of this ability to zoom in and see what to the naked eye is an invisible aspect of a life form. Later in the semester I was attending a ceremony with my family. Throughout the ceremony, I began to understand that our ways and this ceremony can function like that microscope in that they provide yet another ability to see an aspect of life that is “unseen.” This ceremony provided space for me to consider the spirit of our plant relatives and the knowledge they have developed over time, through relationship and movement. Further, they showed me how through patience, observation, listening, and practice I can be a good relative not only to them, but to others (people, waters, animals, etc.).

We should all consider ourselves to be in stewardship roles. To be in a stewardship role is to understand that you have a responsibility, as we all do, to be good relatives to wherever it is that we find ourselves and to whomever your community is comprised of. Sometimes reframing helps us to understand how to be in these positions and then what the impact of us being in them means. For example, Jack posed a question about how Native community members understand accessing stewardship roles and careers. And with this, do they see education as that pathway and if not, why not? I did not originally understand that education was the pathway to do something in this space. It took time for me to understand that I could utilize education to support me in being a good relative.

Dina: Why is it important for Native people to be in green collar jobs everywhere?

Jack: I think it is important for Natives to be in green jobs nationwide because of our relationship and the inherent responsibility felt to protect and provide for air, land, and water. I also think it is interesting that many Native people do not acknowledge their connection to air, land, and water as they think about employment. I believe there are many Native people who can work in a green economy and are not being supported in finding their way to those jobs that both currently exist and need to be created. I think that there are jobs in a green economy that are not developed based upon the way Native people see or believe in protecting and providing for community and nature. The act of protecting nature and natural resources is a critical act for overall community wellness and if not those who hold an intensive identity structure don’t align with being responsible for the ecological world around them, then who?

Kai: I think a different way to look at this is to consider how we think about economies and to talk about what Indigenous models and values function (or don’t function) within the current economic systems. Further, we should ask what Indigenous economies look like? Green collar jobs are one approach, but we still follow a model of extraction that requires more critical investigation. This industry will not be changing overnight. Yes, we want to see Native people in these roles. We also do not just want to see people placed in those roles based solely to meet a diversity quota. Placement should include listening to and actualizing the ways that Indigenous people understand relationship and stewardship. More than this though, we need to reimagine economies, stewardship actions and alignment of these spaces from an Indigenous perspective.