By Clarice Begaye (Diné)

Diné College

Graduate 2023

This is the story of a father who instilled in his daughter the value of education in its many forms, and a mother and grandmother who paved the way through their teachings. Read the first part of the story, then join us as we follow along with our storyteller in this next segment.

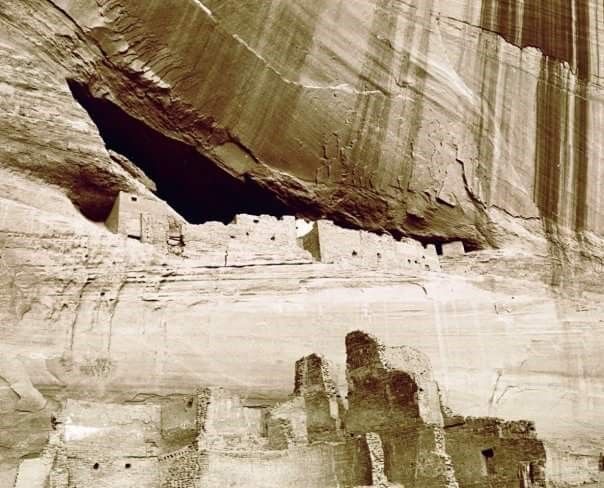

My father’s origins serve as the starting point. He was brought up in Finger Point, situated within the boundaries of the Teesto Chapter. The road leading to Finger Point is characterized by rough terrain, consisting of volcanic rock and sharp fragments of gray stones. It remains untouched by modern amenities such as electricity, water lines, and paved roads. Having paved roads is considered a luxury. Like my father, I learned to appreciate the simplicity of life without the conveniences of modern utilities such as running water, lights at the flick of a switch, or an indoor bathroom. We used to watch TV with rabbit ears, powered by a car battery only at night. During the day we focused on household chores, attending to the garden and the livestock. This place had everything we needed at times when there was no need for a trip to the grocery store.

I have always felt sympathy for my father. His upbringing was tough. His mother passed away shortly after his birth, and he had no one to shelter him. His father and older siblings couldn’t take care of him due to their circumstances. Being born into a sizable family, his salvation arrived in the form of an individual we affectionately referred to as “old grandma” because she was the eldest elder. This remarkable woman happened to be my father’s great-grandmother, Annie. Upon taking custody of my father, she informed my grandfather that he could not reclaim him, as he now belonged to her. Although she had never experienced the joy of raising the children she had carried in her womb, as she had experienced miscarriages and stillbirths, she selflessly nurtured numerous youngsters whose own relatives were unable to care for them. She was a woman of great strength and resilience. She came from a long line of healers and was a traditional Navajo doula, using moon stones to help position children in the womb. She was also knowledgeable about herbs and other techniques used to help women before and after childbirth. She once said the reason she couldn’t have children might have been because she saved and helped many other children and their mothers.

My father would tell me stories of his childhood, when he lived on a vast expanse of land, with his nearest neighbor at least half a mile away. This gave him the freedom to move around as he pleased. His stepfather, Hosteen Bitsi Lakai Begay, taught him about horses and cattle. When his stepfather was away at work, my great-grandmother, a highly skilled weaver, provided a sustainable source of income for my father and herself by creating exceptional rugs and horse blankets. The community also supported each other by growing a community garden called Taa’wl hogan, where they harvested and shared various vegetables and fruits. Some members sold their harvest, while others preserved it to last through the winter. I was amazed to hear how they were able to preserve their harvest without refrigeration, making it last for several months. It is a testament to their impressive ingenuity.

In the 1960s, the residents of Finger Point were forced to relocate due to land disputes instigated and perpetuated by state and federal governments and energy companies to access natural resources that the land held. These residents lost a type of freedom that open space provides, so different from a cookie cutter box living filled with steel, concrete, and pavement. A handful of courageous women stood their ground and refused to be displaced. This exemplifies why women hold great significance and are regarded as leaders within the community. Shockingly, some of these women were treated like livestock rather than human beings, confined to the back of ranger trucks along with their livestock, just for safeguarding their homes and livestock. Among these brave women was a close friend of my grandma Annie. I was told about an old photograph that depicted this degrading situation. The news headlines used strife between two tribes as a smoke screen to obscure the true underlying issue of capitalism. Land and resources acted as a catalyst, resulting in a far from pleasant aftermath. Yet many think such events only happened during the “Indian Wars.”

Unbelievably, I went through the same experience as my parents and grandparents. Government officials arrived asking us to relocate, offering amenities like a new home at no cost. In 1991, I remember a red notice was hung on our door by a ranger, sealing our fate. Most people couldn’t refuse the offers, so only a handful of us remained. My mother went through a similar ordeal during her teenage years in Echo Canyon, a different part of the reservation. Her childhood home, like our home along with some of our possessions, was bulldozed into rubble. She would often reminisce about how my grandfather’s military medals were lost in the chaos, except for his Purple Heart that he carried with him. He had received for his service in the Philippines during World War II.

Relocation has had a profound impact on me, far greater than I could have ever anticipated. It has provided me with a deep understanding of the harsh realities of life: The constant movement from one place to another, relying on the hospitality of various relatives, and the agonizing wait for a housing opportunity from tribal housing. I discovered that applications move at a snail’s pace and that inadequate housing on the reservation exists. Through this process, I developed a strong sense of empathy towards my ancestors who were forcibly taken away during the Long Walk, leaving behind not just physical structures but an entire way of life. I now understand why my ancestors’ shed tears upon seeing Mt. Taylor in the distance: they were grateful to have survived. It symbolized a series of battles to come and initiated the loss of a cherished way of life. This event held great significance for future generations, as it emphasized the value of a western education. As my great-grandfather once conveyed to my grandfather, certain conflicts would be resolved through intellectual discourse and the pursuit of knowledge. He advised us to embrace learning and adjust accordingly, while always remaining mindful of our roots and heritage.

Join us next week for the third and final segment of Keepers of the Flame.