Education was never the point when American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hawaiian children were taken from their families by agents of the U.S. government and were forced to travel far from the only homes they had ever known to live at boarding schools.

Education was never the point when American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hawaiian children were taken from their families by agents of the U.S. government and were forced to travel far from the only homes they had ever known to live at boarding schools.

Education was never the point when strangers cut Native children’s hair, burned their clothing, washed their tiny bodies with harsh lye soap, forbade them to speak their languages or practice their traditions, and assigned them new names.

According to the Federal Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report published by the U.S. Department of the Interior after a year-long investigation into Federal Indian boarding schools at the direction of Secretary Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna), whose own grandparents were boarding school survivors, the real mission of boarding schools was cultural erasure. The ultimate goal was dispossessing American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hawaiian people from their land to ensure the expansion of the United States.To understand the malignant purpose of boarding schools, look no further than their cemeteries. Schools should not have cemeteries. Yet the investigation uncovered 53 burial sites with the remains of 500 American Indian/Alaska Native and Hawaiian children at the 408 Federal schools (along with more than 1,000 other federal and non-federal institutions) that operated between 1819-1968 in 37 states (and then-territories), and 27 schools in Alaska and seven in Hawaii. More site discoveries are expected as the research continues.

Boarding schools used violence and fear to attempt to assimilate Native children—and child manual labor and tribal trust accounts supplemented federal funding to keep them running. There too many of our relatives were beaten, starved, sexually abused, and deprived of medical care. Many died or committed suicide. And those who survived would never be the same—which was the Federal government’s objective.

By “educating” Native children in the white man’s ways, boarding schools attempted to erase their ties to their tribal nations and the land. As students were in essence hostages, the government hoped Native parents would not fight while their children were held at school. And as the students’ ties to family and land eroded, the Government hoped the Indian wars would end and they would have access to Native territories to continue expansion.

What happened at boarding schools was not education. Native people have always educated— and continue to educate—our youth in our languages, medicine, soil management, forestry, watershed management, animal husbandry, meteorology, astronomy, navigation, self-governance, and more. We taught—and teach—our generations how to care for each other, participate as communities, and tend to our bodies, minds, and spirits. Native people have been introducing our young to the joy of self-actualization through learning for centuries.

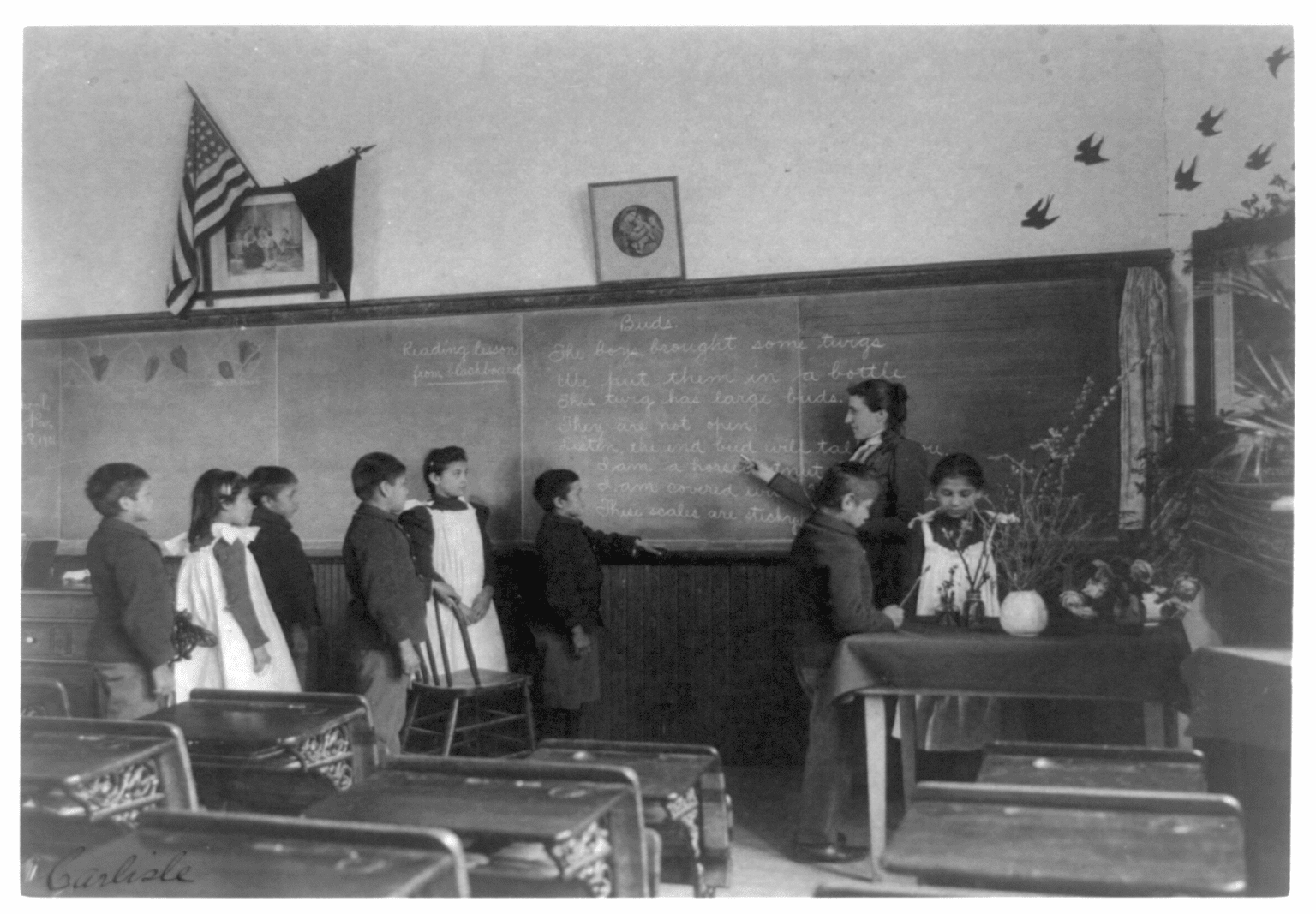

American Indian boarding school students. U.S. Library of Congress.

Born during the Civil Rights Movement, tribal colleges and universities were established as higher education institutions where Native students can continue their learning centered on place, culture, and tradition. TCUs are institutions where students’ identities as Native people are honored, and where they can fully explore identities while getting a quality higher education.

As we confront the horrific legacy of boarding schools and its impact on our Native communities, please do not conflate the Federal government’s mission of assimilation with real education and learning. At the American Indian College Fund, we say that education is the answer: to building self-governing communities and nations; to cultural, spiritual, and intellectual growth; to economic growth and security; to maintaining and preserving our identities and values as Native peoples for future generations; and to healing from historical trauma. In the wake of 150 years of the boarding school system that attempted to estrange Native peoples from their cultures, languages, traditions, and spiritual beliefs, we as Native people have resisted and persisted precisely because of all of the things that boarding schools attempted to erase—and because of our belief in place-based education.

As we as citizens interrogate the historical record to seek the truth and have the Federal government acknowledge the experiences of our relatives in its care, we at the American Indian College Fund applaud the report’s recommendation to have community members share their experiences and the resulting impacts. We know there is healing in storytelling. We particularly support the recommendation to have Federal Indian policy today support the revitalization of Tribal languages and cultural practices to counteract nearly 200 years of policy that was intended to destroy them. The American Indian College Fund has been involved in this important work and continues to see how a culturally based education empowers and grounds our students as they grow personally and professionally. We also support the Department of Interior’s recommendation that the investigation continue under the appropriation authority Congress has granted under the fiscal year (FY) 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L 117-103). We agree that the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the ability to obtain and review documents and restricted funding due to a continuing resolution for much of the past year have made the investigation incomplete.

We believe the history curriculum nationwide should include the truth to ensure this never happens again. And we believe all Native children have a right to have an education based in Native values, where they can reach their potential as members of their sovereign nations, free to embrace their languages, cultures, and traditions, and to take their places as members of their sacred communities—on this—their land—in Indian Country and their native Alaska, and Hawaii.